JavaScript - Getting Started with Promises

There are many times when an operation in a program or on a webpage is requested, but the results of the request aren’t immediately available for further processing. In cases like these, the operation is considered to be asynchronous. To handle this specific situation more smoothly, JavaScript has an object called a Promise that represents the eventual completion or failure of the asynchronous operation and provides the means for programmers to work with asynchronous operations and data.

The problem

Before diving into promises and their use, it’s best to understand the problem they help to solve. Often in JavaScript one function depends on the result of another function before it can return its own result. For example, consider a complex set of mathematical operations that execute one after the other and depend on the result of the previous operation before the next can execute.

const add = (n1, n2) => {

return n1 + n2;

};

const square = (n) => {

return n * n;

};

let v1 = add(5, 8);

let v2 = square(v1);

console.log(v2); // 169

This code executes in order from top to bottom. Each function is able to return a result before the next function that uses the result executes. However, there are situations where a function will take some time to complete before returning a result and JavaScript doesn’t wait as it executes the code.

const add = (n1, n2) => {

setTimeout(() => {

return n1 + n2;

}, 2000);

};

const square = (n) => {

return n * n;

};

let result = add(5, 8);

console.log(square(result)); // NaN

The difference in the code above is that the add function has a delay of 2 seconds before it completes its operation and returns a result. By the time that has happened, the remainder of the code has already run. At the moment the second function executes, the variable v1 has a value of undefined, which when passed into the square function returns NaN, which is outputted before the first function can return its calculated value.

Callbacks to the rescue

Before promises were added to JavaScript with ES6, the best way to handle asynchronous operations was by using callbacks. A callback is basically a function that is passed as an parameter to another function and is then called within the body of the first function. A common reason to do this is to handle asynchronous data retrieval - where progression of the program depends on data that can take some time to be returned and made available to the next part of the program. A typical example is asynchronously waiting for data from an api that is needed by another part of the program to continue.

For example, the example above currently fails to handle the case where the square function is called before the add function has completed. To solve this, the square function could be called as a callback from the add function, like so:

const add = (n1, n2, callback) => {

setTimeout(() => {

let calculation = n1 + n2;

callback(calculation);

}, 2000);

};

const square = (n) => {

return n * n;

};

add(5, 8, (result) => {

console.log(square(result));

});

The example above executes the add function asynchronously, and then passes the result of the add function to the square function. The square function then uses the result of the add function to calculate the square of the result. In this case, even though there is a delay of 2 seconds, the square function is able to use the result of the add function since the callback depends on the result of the add function.

The simple example above isn’t too difficult to understand. However, it’s possible that an operation may require several steps before it is finished, and this would require multiple callbacks. For example, consider the following code:

const add = (n1, n2, callback) => {

setTimeout(() => {

let result = n1 + n2;

callback(result);

}, 2000);

};

const multiply = (n1, n2, callback) => {

setTimeout(() => {

let result = n1 * n2;

callback(result);

}, 2000);

};

const subtract = (n1, n2, callback) => {

setTimeout(() => {

let result = n1 - n2;

callback(result);

}, 2000);

});

const square = (n) => {

return n * n;

};

add(5, 8, (result) => {

multiply(result, 5, (result) => {

subtract(result, 8, (result) => {

console.log(square(result));

});

});

});

Although this example doesn’t look overly complex, it does show how the callback pattern can become deeply nested and with more complex tasks than shown above, it can become very difficult to understand what is happening. Thankfully, the developers of JavaScript recognized this problem and proposed a solution for it.

Improving on callbacks with a Promise

As described above, the problem with callbacks is that they can become complex and difficult to maintain and/or understand. Multiple callbacks nested within each other can quickly become unmanageable, sometimes called the pyramid of doom. Additionally, callbacks don’t offer any built-in error handling when an asynchronous request does not complete successfully. This functionality has to be added by the developer.

The introduction of the Promise object helps to address these problems and provide a more elegant way of handling asynchronous operations. A Promise represents the eventual completion or failure of an asynchronous operation and provides the means for the programmer to work with asynchronous operations and data.

The core idea behind a promise is that while an asynchronous operation is in process, it will return an intermediate value that can be used to track the progress of the operation. Once the operation is complete, the promise will either resolve to a final value or not. This value can be used to determine the success or failure of the operation.

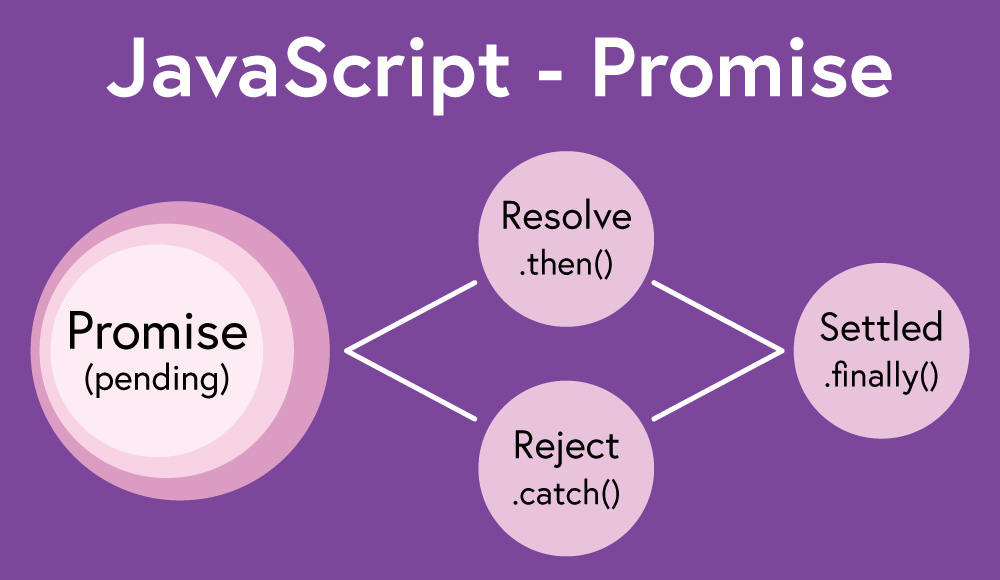

A core concept of promises are the different states that a promise can experience:

- pending - the promise is in its initial state, neither resolved (fulfilled) or rejected

- fulfilled (resolved) - the promise operation was completed successfully

- rejected - the promise operation failed

Entering into either the resolved or rejected option will trigger their associated handler, which are processed by calling the Promise then method.

Working with Promises

Making use of promises can be done by using pre-existing promises, typically in the form of external libraries or apis that can be consumed as promises or by creating a new Promise with the constructor. By creating a promise from scratch, it’s possible to understand what a promise is doing internally.

The following example shows the basics of how to create a new promise. A promise expects an executor function that contains custom code to instruct the promise how to either resolve or reject the promise. The executor function includes signatures for a resolve function and reject function, which can be used to pass a value to be handled by the corresponding resolve and reject functions.

const myPromise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve('promise is resolved');

});

myPromise.then((result) => {

console.log(result);

});

A more complex example shows how to add control flow to determine whether or not to use the resolve or reject function based on the result of a logical operation within the executor function.

const additionPromise = (number1, number2) => {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

if (typeof number1 === 'number' && typeof number2 === 'number') {

let result = number1 + number2;

resolve(result);

} else {

reject('Please use numbers');

}

}, 2000);

});

};

additionPromise(5, 7)

.then((result) => {

console.log(result);

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error);

})

.finally(() => {

console.log('promise completed');

});

// 12

// promise completed

additionPromise(5, 'hello')

.then((result) => {

console.log(result);

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error);

})

.finally(() => {

console.log('promise completed');

});

// Please use numbers

// promise completed

The promise above demonstrates a few different concepts. First, The function additionPromise is a regular function that accepts two parameters and returns a promise. The promise is composed of an executor function that includes a resolve and reject function handler. The executor also contains a setTimeout function to demonstrate the asynchronous nature of promises. If the passed parameters return true for the logical operation, the numbers are added and the resulting variable is passed to the resolve function, which is can be called by the then method.

If the logical operation returns false, then the reject function is called, passing in a string value. The way that this is handled is by calling the catch method on the promise. If the reject function is called, the promise will bypass all resolve (including chained) then methods and use the catch method. Lastly, an optional finally method can be called. This method will be called no matter if the promise is resolved or rejected.

Chaining promises

As mentioned above, promises can be chained together, which allows multiple promises, which include multiple processes, to be handled before returning a final result.

const additionPromise = (number1, number2) => {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

if (typeof number1 === 'number' && typeof number2 === 'number') {

let result = number1 + number2;

resolve(result);

} else {

reject('Please use numbers');

}

}, 2000);

});

};

const squarePromise = (number) => {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

if (typeof number === 'number') {

let result = number * number;

resolve(result);

} else {

reject('Please use a valid number');

}

}, 2000);

});

};

additionPromise(2, 4)

.then((result) => {

return squarePromise(result);

})

.then((result) => {

console.log(`final result: ${result}`);

})

.catch((error) => {

console.log(error);

})

.finally(() => {

console.log('promise operation completed');

});

// final result: 36

// promise operation completed

The example above shows how to consume multiple promises and each resolves to return a result that can be used by the promise to step through an asynchronous operation.

Conclusion

Promises are tricky to understand if the only way they are encountered is by trying to consume them. By creating a promise and understanding how they’re composed, it’s much easier to understand the best steps to take to use them.